I found a

copy online of the NASA publication, "Voyage to Jupiter," by David Morrison and Jane Samz. This publication provides some great insights into the Voyager encounters with Jupiter in 1979, the science investigations the two spacecraft performed and the new knowledge they obtained. The document also has a day-by-day account of the activities of the spacecraft and the science and engineering teams for both Voyager encounters.

Below is an excerpt covering the Io encounter by Voyager 1,

30 years ago today. Don't forget to check out

the post immediately below this one for some of my own thoughts and a nice animation of the encounter with Io. Later this week, I will post more about the discovery of active volcanism on Io, which occurred a few days after the flyby, and on how scientists viewed Io and its geology following the encounter.

Monday, March 5. Many celebrities, including the Governor of California, spent the night at JPL to witness the historical occasion. In Washington, D.C., as special TV monitor was set up in the White House for the President and his family.

Shortly before closest approach to Jupiter, Voyager began its intensive observations of Io. Much of this information, taken while the Australian station was tracking the spacecraft, was recorded on Voyager's onboard tape-recorder for playback later that day. But even before the results of that imaging were known, Larry Soderblom was calling Io "one of the most spectacular bodies in the solar system." As more and more vivid photos of Io appeared on the monitors, members of hte Imaging Team in the Blue Room buzzed with excitement. "This is incredible." "The element of suprised is coming up in every one of these frames." "I knew it would be wild from what we saw on approach but to anticipate anything like this would have required some sort of heavenly perspective. I think this incredible."

At 7:35 a.m. Voyager was scheduled to pass through the flux tube of Io, the region in which tremendous electric currents were calculated to be flowing back and forth between the satellite and Jupiter. Norm Ness suggested, after examining the magnetometer data, that Voyager skirted the edge of the flux tube, and that the current in the tube was about one million amps. As the flux tube results were received, champagne bottles began to pop in the particles and fields sciences offices, in celebration of the successful passage through the inner magnetosphere. Meanwhile, at 7:47 a.m., closest approach to Io occured, at a range of only 22 000 kilometers. Voyager was 25 000 times closer to this satellite than were the watchers on Earth.

At 8 a.m. a special press conference was held to mark the successful Jupiter flyby. Noel Hinners, Associate Administrator for Space Science and the highest ranking NASA official present, congratulaed all those who made the Voyager Mission a success. The encounter was the "culmination of a fantastic amount of dedication and effort. The result is a spectacular feat of technology and a beginning of a new era of science in the solar system. Just watching the data come in has been fantastic. I had a fear that things on the satellites were going to look like the lunar highlands. Nature wins again. If we're going to see exploration of this nature occurring in the 1980s and 1990s we must continue to expound the results of what we're finding here, the role of exploration in the history of our country, what it means to us as a vigorous national society."

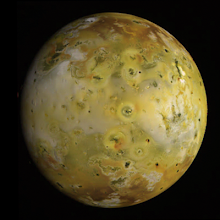

At the regular 11 a.m. press briefing, Brad Smith glowed. "We're recovering from what I would call the most exciting, the most fascinating, what may ultimately prove to be the most scientifically rewarding mission in the unmanned space program. The Io pictures this morning were truly spectacular and the atmosphere up in the imaging area was punctuated by whoops of joy or amazement or both." The new color photo of Io taken the night before was released, showing strange surface features in tones of yellow, orange, and white. The image defied description; the Imaging Team used terms like "grotesque," "diseased," "gross," "bizarre." Smith introduced the picture with the comment, "Io looks better than a lot of pizzas I've seen." Larry Soderblom added, "Well, you may recall [that we] told you yesterday that when we flew by we'd figure all of this out. I hope you didn't believe it."

One thing was certain: There were no impact craters on Io. Unless the satellites of Jupiter had somehow been shielded from meteoric impacts that cratered objects such as the Moon, Mars, and Mercury, the absence of craters must indicate the presence of erosion or of internal processes that destroy or cover up craters. Io did not look like a dead planet. Imaging Team member Hal Masursky, looking at the "pizza picture, estimated that the surface of Io must be no more than 100 million years old -- that is, some agent must have erased impact craters during the last 100 million years. This interpretation depended on how often cratering impacts occur on Io. No one could be sure that there had been any interplanetary debris in the Jovian system to impact the surfaces of the satellites. Perhaps none of them would be cratered. The forthcoming flybys of Ganymede and Callisto would soon provide this information.

As encounter day drew to a close, celebrations took place all over JPL. For many, however, the excitement was tempered by exhaustion. After 48 hours of intense activity, sleep was imperative for some. But the close approach to Callisto was still to come, as was an examination of the data already received.

Link: Voyage to Jupiter [eric.ed.gov]

I found a copy online of the NASA publication, "Voyage to Jupiter," by David Morrison and Jane Samz. This publication provides some great insights into the Voyager encounters with Jupiter in 1979, the science investigations the two spacecraft performed and the new knowledge they obtained. The document also has a day-by-day account of the activities of the spacecraft and the science and engineering teams for both Voyager encounters. Below is an excerpt covering the Io encounter by Voyager 1, 30 years ago today. Don't forget to check out the post immediately below this one for some of my own thoughts and a nice animation of the encounter with Io. Later this week, I will post more about the discovery of active volcanism on Io, which occurred a few days after the flyby, and on how scientists viewed Io and its geology following the encounter.

I found a copy online of the NASA publication, "Voyage to Jupiter," by David Morrison and Jane Samz. This publication provides some great insights into the Voyager encounters with Jupiter in 1979, the science investigations the two spacecraft performed and the new knowledge they obtained. The document also has a day-by-day account of the activities of the spacecraft and the science and engineering teams for both Voyager encounters. Below is an excerpt covering the Io encounter by Voyager 1, 30 years ago today. Don't forget to check out the post immediately below this one for some of my own thoughts and a nice animation of the encounter with Io. Later this week, I will post more about the discovery of active volcanism on Io, which occurred a few days after the flyby, and on how scientists viewed Io and its geology following the encounter.

No comments:

Post a Comment