Behold therefore, four stars reserved for your famous name, and those not belong to the common and less conspicuous multitude of fixed stars which, with different motions among themselves, together hold their paths and orbs with marvelous speed around the planet Jupiter, the most glorious of all the planets, as if they were his own children, while all the while with one accord they complete all together mighty revolutions every twelve years around the center of the universe, that is, round the Sun.Three Little Stars

- From Galileo's Sidereus Nuncius (trans. by Edward S. Carlos)

In early January 1610, Galileo had just finished up an incredible series of observations of the Moon, the Milky Way, and several stellar nebulae. In the case of the Moon, his 20-power telescope revealed the Moon's cratered and mountainous surface, showing that it was not smooth and perfect as stated in the Aristotelian world view, but was in fact, quite rough. Galileo discovered a multitude of stars, far more than could be seen with the naked eye, within the "clouds" of the Milky Way, on the belt of the constellation Orion, and within nebulae and star clusters such as the Orion Nebula, Beehive Cluster, and the Pleiades. During the first week of January 1610, Galileo drafted a letter to Galileo's Florentine friend, Enea Piccolomini describing these observations along with details on how best to operate the telescope for astronomical viewing, for example, suggesting the use of a stand for the telescope to prevent inadvertent hand motions from ruining observations. Galileo set aside the letter for a few days, picking it back up on the evening of January 7, 1610.

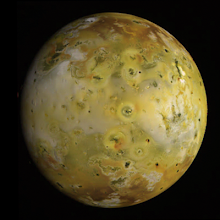

In early January 1610, Galileo had just finished up an incredible series of observations of the Moon, the Milky Way, and several stellar nebulae. In the case of the Moon, his 20-power telescope revealed the Moon's cratered and mountainous surface, showing that it was not smooth and perfect as stated in the Aristotelian world view, but was in fact, quite rough. Galileo discovered a multitude of stars, far more than could be seen with the naked eye, within the "clouds" of the Milky Way, on the belt of the constellation Orion, and within nebulae and star clusters such as the Orion Nebula, Beehive Cluster, and the Pleiades. During the first week of January 1610, Galileo drafted a letter to Galileo's Florentine friend, Enea Piccolomini describing these observations along with details on how best to operate the telescope for astronomical viewing, for example, suggesting the use of a stand for the telescope to prevent inadvertent hand motions from ruining observations. Galileo set aside the letter for a few days, picking it back up on the evening of January 7, 1610. That evening, an hour after sunset, Galileo aimed his 20x telescope, with a newly masked objective lens, toward the planet Jupiter, at the time near opposition and in the midst of its retrograde loop in the night sky. In this case he observed three stars forming a line with Jupiter, parallel to the ecliptic. Two of these stars were to the lower left (east) of Jupiter and another star was to the upper right (west) of the planet. He noted this in the conclusion of his letter to Piccolomini:

That evening, an hour after sunset, Galileo aimed his 20x telescope, with a newly masked objective lens, toward the planet Jupiter, at the time near opposition and in the midst of its retrograde loop in the night sky. In this case he observed three stars forming a line with Jupiter, parallel to the ecliptic. Two of these stars were to the lower left (east) of Jupiter and another star was to the upper right (west) of the planet. He noted this in the conclusion of his letter to Piccolomini:... and only this evening I have seen Jupiter accompanied by three fixed stars, totally invisible by their smallness, and the configuration was in this form [graphic shown matches the configuration displayed in the screenshot from Celestia at left] nor did they occypy more than one degree of longitude. The planets are seen very rotund, like little full moons, and of a roundness bounded and without rays. But the fixed stars do not appear so...On January 7, 1610, Galileo discovered what we call today the Galilean moons, believing them at the time to be fixed stars behind Jupiter. When I first read this passage, I assumed he was referring to the moons as "The planets" in that last section, hence my anniversary message earlier today. However, re-reading that and understanding the timing of when that was written, the very night he made his first observation of these satellites, he was actually referring to planets like Venus, Jupiter, or Mars as "little full moons", and that these "fixed stars" do not appear like that. This again drives home the point that on January 7, the day of discovery, Galileo hadn't figured out what he found, but it was enough for him to keep making observations over the following days.

A quick note: Galileo refers to having seen three little stars, not four. In fact, he did see all four Galilean satellites. Ganymede was the lone star to the west of Jupiter and Callisto the star furthest east. The eastern star closest to Jupiter was actually two moons, Io and Europa, too close together for Galileo's low-powered telescope to separate.

Over the following days, Galileo continued to observe Jupiter. On January 8, he found three moons again, this time all to Jupiter's west with about equal spacing (from Galileo's Sidereus Nuncius, with moon labels added by me):

This observation startled Galileo, "Yet my surprise began to be excited, how Jupiter could one day be found to the east of all the aforementioned fixed stars when the day before it had been west of two of them." Jupiter was moving retrograde, as expected being at near opposition, and if anything, Jupiter should be to the west of all three stars. Galileo even noted that he hadn't even considered the fact that all three were now closer together. I should point out that a fourth Galilean satellite, Callisto, could have been seen to the far east of Jupiter, but was apparently outside Galileo's field of view and thus wasn't recorded.

After he was clouded out on January 9, he continued his observations on January 10, finding two stars (Callisto and a close conjunction of Ganymede and Europa) to the east of Jupiter. Io was caught up in the glare of Jupiter in Galileo's telescope for him to observe it that night, as he suspected. At this point, as he noted in his Sidereus Nuncius, Galileo realized that the orientations of the stars with respect to Jupiter changed, not due to the motion of Jupiter, which would have to be chaotic, first moving west, then east, then west again on successive nights, but due to the motions of these stars themselves. On January 11, he noted two stars to the east of Jupiter (Ganymede and Callisto; Io and Europa were transiting Jupiter at the time and were thus lost in the planet's glare). Galileo even noted the difference in brightness between Ganymede and Callisto. With this observation, according to his Sidereus Nuncius, Galileo came to the conclusion that these were not stars at all, but little planets in orbit around Jupiter, just as the planets revolved around the Sun. He also deduced that there were not three bodies moving about Jupiter, but four, even despite the fact that he hadn't solidly observed all four at once to this point. Some historians, such as Stillman Drake, propose that these conclusions, that Jupiter was orbited by four little planets, were actually reach several days later, and that he simply put his those notes in the wrong place in his notebook, which were then further transcribed in his book two months later.

Cosmica Sidera

Galileo continued to jot down his observations on the draft of a letter he had written to Venetian Doge Leonardo Donato back in August 1609 (promising not to show his innovations to another foreign power...oh, like Tuscany...). On January 12, Galileo observes Jupiter for a more extended, first observing the planet and two of its moons on each of the planet, Ganymede to the east and Europa to the west, then seeing Io emerge from Jupiter's glare to the planet's east. Callisto remained hidden from view in the glare. By this point, certainly Galileo could make the conclusion that the "stars" moved perceptively during a single observing run. The following day, January 13, Galileo observed and recorded all four Galilean satellites for the first time, with Europa to the east of Jupiter and Ganymede, Io, and Callisto, respectively, to the west. So it is on January 13 that Galileo could obviously conclude that there were four stars, instead of three.

Galileo continued to jot down his observations on the draft of a letter he had written to Venetian Doge Leonardo Donato back in August 1609 (promising not to show his innovations to another foreign power...oh, like Tuscany...). On January 12, Galileo observes Jupiter for a more extended, first observing the planet and two of its moons on each of the planet, Ganymede to the east and Europa to the west, then seeing Io emerge from Jupiter's glare to the planet's east. Callisto remained hidden from view in the glare. By this point, certainly Galileo could make the conclusion that the "stars" moved perceptively during a single observing run. The following day, January 13, Galileo observed and recorded all four Galilean satellites for the first time, with Europa to the east of Jupiter and Ganymede, Io, and Callisto, respectively, to the west. So it is on January 13 that Galileo could obviously conclude that there were four stars, instead of three.I notice on Wikipedia that this is listed as the discovery date for Ganymede, while January 7 is listed for the other three. While January 13 was the date that Galileo first observed all four satellites at the same time, by that date, he had observed all four, though just not all at the same time. You could reasonably argue that for any of the moons, that three were discovered on January 7 and the fourth on January 13, but the fact remains that on January 7, all four were visible to Galileo and noted by him (though two were too close to be separated).

Galileo's first detection of motion between the moons, evidence that the moons orbited Jupiter, came on January 15 when Galileo observed all four moons to the west of Jupiter. Over the course of four hours that night, Galileo observed Io moving east and slowly become lost in the glare of Jupiter. Ganymede and Europa, the middle of the two moons seen, were observed to come closer together as the night progressed. From this and his earlier observations, Galileo was able to conclude that these four stars actually orbited the planet Jupiter, just as the planets orbit the Sun.

For Tomorrow

Galileo would continue to observe Jupiter and the moons he would christen the Cosmic Stars, after his former pupil and future employer, Cosimo II de' Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, for the next month and a half, until March 2, 1610. At that point, he published his findings, the rough terrain of the Moon, the countless stars of the Milky Way, and the new Jovian planets, in Venice as Sidereus Nuncius, or The Starry Messenger. Tomorrow, January 8, we will discuss this ground-breaking book and its reception by the public, Church, and fellow scientists.

Link: Galileo's First Jupiter Observations (comparing Galileo's records with simulated views) [home.comcast.net]

Link: The Galileo Project | Satellites of Jupiter [galileo.rice.edu]

Link: JPL Galileo Discovery Page [www2.jpl.nasa.gov]

I'm contacting people about fixing the respective Wikipedia articles, only how do you explain on each of them that they were all "discovered" the same day (but that Europa and Io were discovered as the same "star").

ReplyDeleteMy argument is that he saw all four on that day, January 7. True, he saw Io and Europa combined as a single star, but nevertheless, his observation of that combined "star" is evidence enough, consistent with modern day models of the motions of the Galilean satellites, that he observed the positions of Europa and Io to within the limit of resolvability for his telescope.

ReplyDeleteTake his January 8 observation. If that had been his first observation, and not January 7, I would argue that he discovered Io, Europa, and Ganymede on that day, and not Callisto, since he failed to observe and record it for that day.

So my argument, is that based on Galileo's own observations, and say, the comparison between them and modern simulations of the positions of the satellites for the times he was observing, the date for the discovery of all four Galilean satellites is January 7, when he recorded the positions of all four moons (with two so close they appeared as a single "star").

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete